The International Court of Justice’s recent advisory opinion on climate change presents Europe with a timely chance to strengthen its legal approach to preventing climate-related harm. The Court affirmed that, under international law, states are required to take action in line with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5-degree target. By establishing a clear and coherent liability framework that aligns with its climate ambitions and legal standards, the EU can offer the legal certainty needed in response to this landmark decision.

To support such a framework and develop additional effective climate policymaking in Europe, it is useful to segment the greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) landscape. To this day segmentation focuses on identifying the actors or sectors responsible for emissions and measuring their output either in absolute terms (CO₂-equivalents) or as a share of total emissions over time. According to the latest UNEP Emission Gap report, annual emissions for global key sectors in 2023 are:

This source-based segmentation guides current policies. However, for effective climate policy, we propose a complementary approach: segmenting emissions by the countermeasure strategy used to reduce overall carbon levels. This solution-focused framework shifts emphasis from who emits to how emissions are addressed. Our analysis proceeds in three steps:

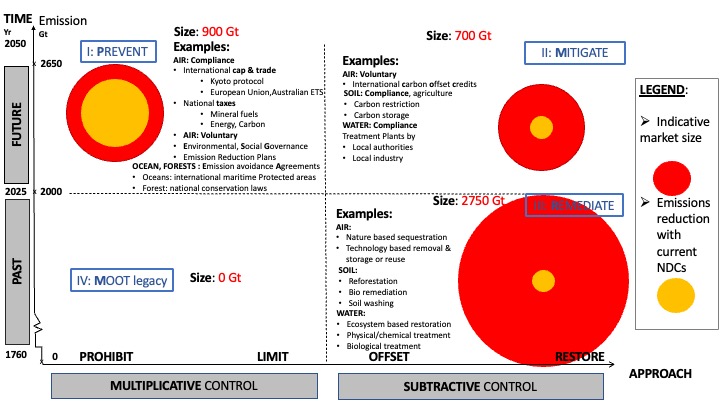

To gain a clear and structured understanding of the total volume of emissions and its share addressed by EU policy and regulation, it is useful to segment existing measures according to their scope and approach. For this, we propose the Prohibit-Mitigate-Remediate-Moot (PMRM) framework that offers a valuable analytical framework by mapping emission countermeasure efforts along two key dimensions: “temporal orientation” (past versus future emissions) and “policy approach” (prohibition and limitation versus offsetting and restoration). This matrix helps identify which categories of emissions are currently regulated and which remain poorly addressed, thereby revealing potential gaps in the global climate policy architecture and highlighting areas where complementary regulatory action may be required.

Time Dimension

The time dimension in the PMRM matrix captures the full span of human impact on the climate, from the onset of industrial-era emissions to the future period during which such emissions are expected to have effects. It distinguishes between past, current, and future emissions, highlighting the need for policies that address both cumulative and anticipated climate impacts.

Approach Dimension

The policy approach dimension of the PMRM matrix contrasts multiplicative and subtractive strategies.

A multiplicative strategy involves reducing the rate at which emissions occur. E.g., a 10% annual reduction allows for 90% of the previous period’s emissions. Or as a formula: 10 × 0.9 = 9. Multiplicative strategies rely on property rights, granting regulated permission to emit, typically via permits or market-based tools and often relying on preventive investments.

Subtractive strategies focus on removing a fixed percentage of the emissions that have already occurred. As a formula: 10 − (10 × 0.1) = 9. Subtractive strategies are grounded in liability rights, protecting third parties with potential legal claims to environmental health.

To summarise, the former authorises emissions under defined conditions, while the latter obliges emitters to offset or restore harm, upholding liability-based accountability.

The two dimensions, time and approach, yield four quadrants (see figure below). This allows for a new type of segmentation, one that focusses on the potential impact for specific intervention areas. The size of each area is calculated based on the 2024 UNEP Emissions gap report, and estimates the additional effort that is needed on top of the current policy scenario to reach the 1.5-degree by 2050 goal affirmed by the International Court of Justice’s opinion.

Estimated intervention potential by segment:

Translating the PMRM market potentials into actionable climate interventions requires a comprehensive alignment of the following overlapping measures and regulatory fields:

Aligning specific measures and regulatory fields to complete the PMRM matrix

In order to link the current opportunity created by the International Court of Justice to a sustainable and effective environmental policy, it is advisable to assess which quadrant existing policies occupy in the PMRM matrix:

Based on this segmentation, it becomes clear that subtractive GHG control has the potential to address 5 to 10 times more GHGs until 2050 compared to multiplicative control, while current policies primarily focus on the latter.

A possible question in climate governance is why subtractive control measures based on liability rights, particularly in Quadrants II and III, remain underdeveloped compared to multiplicative measures in Quadrant I. In our view, the assessment is clear: recent legal developments provide a strong basis for reconsideration. Cases such as “KlimaSeniorinnen v. Switzerland”, “Lliuya v. RWE AG”, and the ICJ’s advisory opinion in the Vanuatu initiative show how liability grounded in human rights, combined with recognition of systemic risk, can enhance the legal role of third parties across borders.2

This emerging “local third-party power”, grounded in established legal principles, is increasingly shaping the actions of Member States and corporate actors across the European Union. As its influence expands, a timely strategic opportunity arises for legislators to strengthen and extend liability-based rights and obligations at both EU and national levels. Such an initiative would help reinforce the legal framework, ensuring that executive and judicial authorities operate in alignment with the Union’s climate objectives - promoting legal coherence, enhancing legal certainty for economic actors, and safeguarding the participation of structurally underrepresented groups in climate governance.

Europe can lead by clarifying responsibilities in the climate transition, including:

Responsibility for the remediation of an estimated 2,750 Gt of historical greenhouse gas emissions cannot be meaningfully assigned to individual citizens or companies, given the diffuse nature of these legacy emissions and their origin in past activities often undertaken without full knowledge of their long-term harm. Rather, the burden lies with society as a whole, and by extension, governments and taxpayers. These legacy emissions constitute a "negative public good"- a collective liability that necessitates a public policy response.

When assessing this public burden, it is critical to avoid simplistic net present value calculations of damages, which may obscure both the historical benefits produced by past emissions and the cumulative societal learning that accompanied them. A more equitable and pragmatic basis for allocating responsibility may lie in a subtractive control approach: defining costs in terms of the actual resources needed to offset emissions and restore affected environments. This offers a clear pathway to identify appropriate legal responsibilities and legitimate third-party actors.

Responsibility for adaptation, disaster preparedness, and broader socio-economic impacts may be more effectively addressed through public investment and development cooperation mechanisms, rather than liability frameworks.

Deferring action, especially in the face of an additional 1600 Gt of projected emissions by 2050, is neither equitable nor sustainable. Long-term mitigation must be financed increasingly by current emitters, ensuring the polluter-pays principle is applied with integrity and foresight.

To allocate these responsibilities, the European Union should implement the following measures:

The development and adoption of such a framework3 would support a more equitable and uniform assessment of both historical and ongoing externalities, particularly greenhouse gas emissions, while providing a coherent legal foundation for climate liability across the EU.

The ICJ’s advisory opinion marks a significant step in clarifying international legal obligations regarding climate change and provides short-term political and long-term legal opportunities. In this context, the PMRM Matrix highlights a significant policy gap: although mitigation and remediation constitute the largest dimensions of the climate change response, there remains substantial untapped potential for regulatory development at the European and international level - particularly with regard to enforceable mechanisms grounded in liability rights.

To close the identified policy gap, European and international legal frameworks should evolve to standardise and mandate subtractive climate measures grounded in liability rights. The European Union is well positioned to lead in this area by advancing binding legal instruments that establish clear liability rules for residual emissions, enhance legal certainty, and enable effective cross-border coordination. Introducing enforceable mechanisms to address both legacy and future emissions aligns with the Union’s climate neutrality objectives, strengthens the integrity of its legal framework, and upholds the principles of environmental justice for both current and future generations.

Erik Tamboryn is a senior economist and a published author. Marc Rosiers is a senior economist with expertise in the agro-food sector. Milan Petit is steward of the Systems Transformation Hub. Janez Potočnik is co-founder of the Systems Transformation Hub, co-chair of the International Resource Panel, and partner at Systemiq.

The content presented in this opinion piece is solely those of the author in their personal capacity, and does not necessarily reflect the position of the Systems Transformation Hub or its members.