Europe has finally grasped what should have been obvious: a circular economy is not optional, it is essential for prosperity, security, and resilience. As President von der Leyen emphasised in her recent State of the European Union: “We also need to make sure that our industry has the materials here in Europe. And the only answer here is creating a truly circular economy. So, we need to move faster on the Circular Economy Act.” 1

While speed is essential, bolder and deeper ambition is needed to create the enabling conditions for the desired transformation. Within the context of the drafting of the Circular Economy Act, this article outlines why a systemic approach is indispensable and what policy missions should guide it.

While materials, everything extracted from the Earth, are the essence of the relationship between humans and the planet, they are being used in wasteful and unjust ways. Over the past 50 years, global material use has more than tripled due to urbanisation, industrialisation and population growth and is the primary driver of the triple planetary crises. Yet the benefits of this growth are distributed unequally and often ineffectively.

The tripling of material use has not translated into similar gains in the Human Development Index. According to the UN International Resource Panel (IRP), 90% of materials are used for four basic human needs - energy, housing, mobility, and food - yet these systems are structured in ways that lock in waste and inequality. This can be seen in how and where materials are used, with high‑income countries consuming six times more materials per person and generating ten times more climate impacts than low‑income countries.2

An environmental transition could therefore only be successful if done hand in hand with a social transition. Decoupling human wellbeing and economic growth from resource use and environmental degradation is a must. The need for a deep system change of all economic sectors, or even better, of all provisioning systems delivering human needs.In this context, the circular economy should be seen as an instrument helping deliver the above-mentioned decoupling in practice. It should be understood as part of the broader economic, societal, and cultural transformations required to deliver the Sustainable Development Goals and other international commitments.

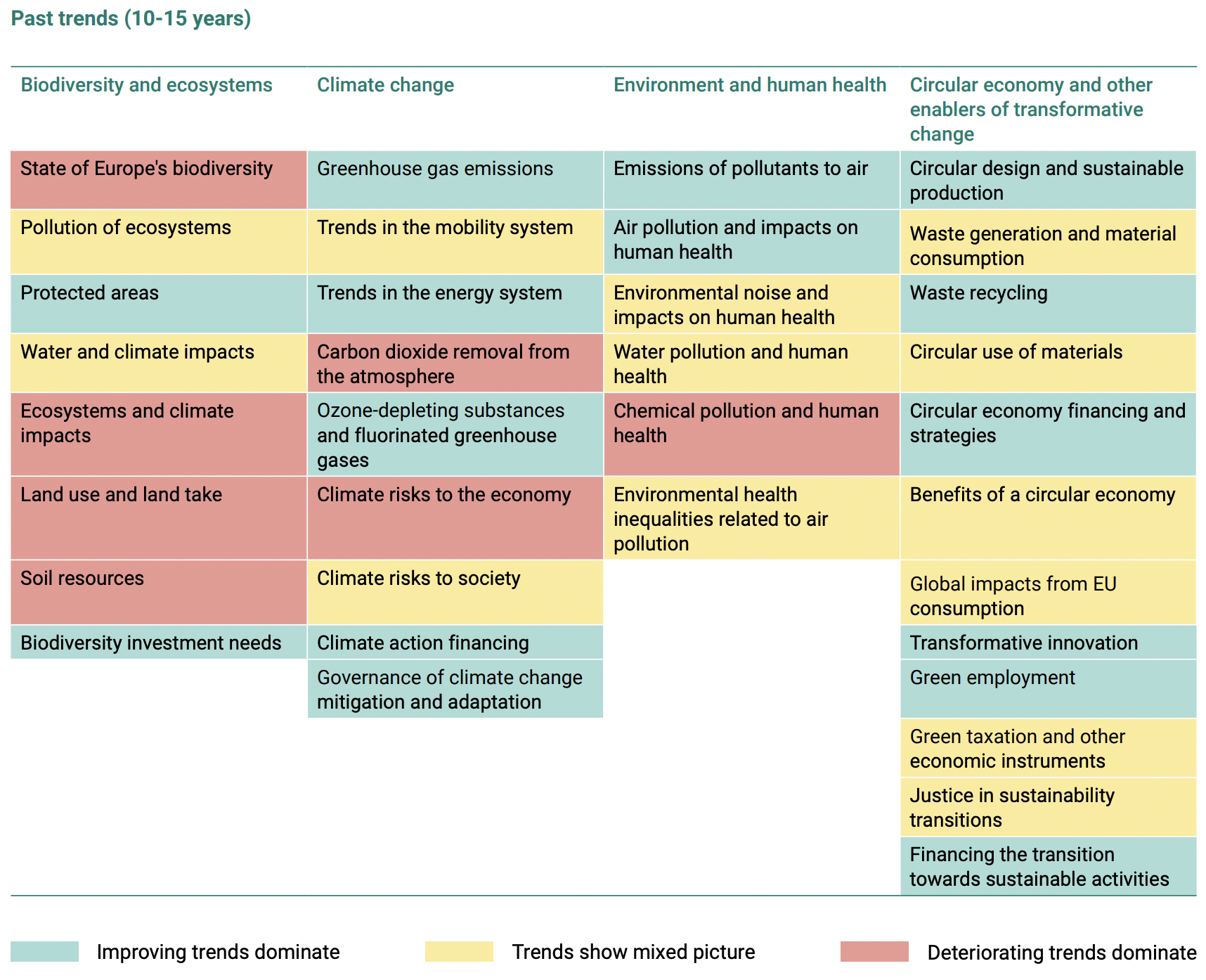

Despite considerable effort, Europe is far from having a circular economy. According to the Europe’s Environment 2025 Report, trends in circular economy from over the last 10 to 15 years appear broadly positive as shown in table 1.3 Yet, the data provided on the circular material use rate tells a different story. In the same period, it only increased from 10.7% to 11.8%. At this rate of change, reaching the EU 2030 target to approximately double the share of secondary raw materials to about 23–24% would take more than a century, not five years.

This contradiction demonstrates that the current policy approach, although valuable, is falling short. What is needed is a systemic approach that makes circular economy practices economically attractive and structurally dominant over the linear economic model.

While there is broad consensus on the need for system change, less agreement exists on what “systemic” means and how to operationalise it.

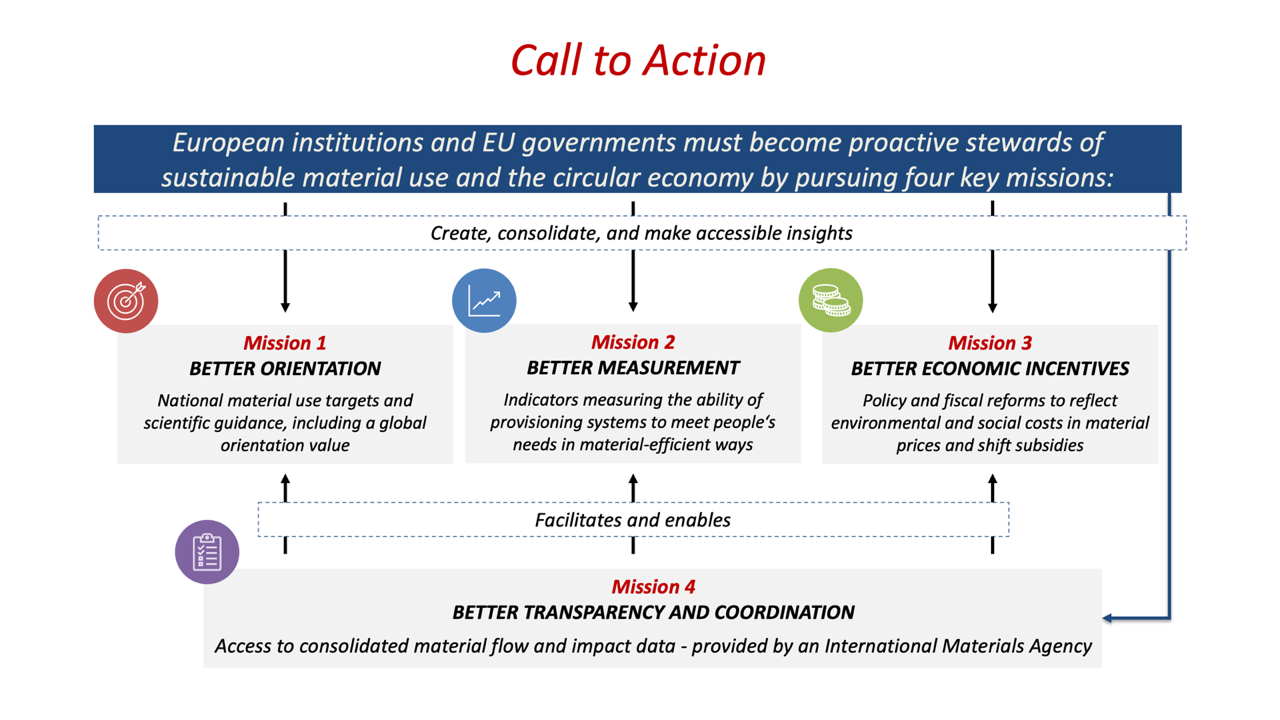

To navigate this debate, The IRP Co‑chairs’ Call to Action, drawing on the GRO24 IRP Policy Recommendations, offers concrete guidance. It identifies four core policy missions that should be embedded in the forthcoming Circular Economy Act to translate ambition into action and deliver system-level outcomes.

High-income countries benefit the most from resource use and are the most responsible for environmental impacts. Meanwhile, many low-income countries still do not consume enough materials to meet basic human needs.

Thus, high-income countries must pursue absolute decoupling: decreasing material use while maintaining or improving wellbeing outcomes. Low and some middle-income countries, where additional material use is still needed to meet people’s basic wellbeing needs, should aim for relative decoupling: sustainably increasing resource use at a slower rate than wellbeing by using resource efficiency and productivity measures.

Following the circular economy hierarchy would provide a strong foundation, with the "refuse" and "rethink" strategies proving particularly critical for integrating the system design solutions currently missing from policy. Focusing on material footprint offers a clear way forward: it would elevate materials management to a central policy priority, signal to governments the need for targeted action, and indicate to the private sector which behaviours will be rewarded.

This approach would complement efficiency with sufficiency and decarbonisation with dematerialisation, while directing overdue attention to demand-side solutions. It would also introduce an essential question into policy debates: who is crossing planetary boundaries through excessive resource use? In doing so, it would advance equity and fairness, helping to close the resource gap between the Global North and Global South.

Our economy was invented to serve humans, not the other way around. Indicators must reflect the ability of the four most resource-intensive provisioning systems - energy, food, mobility, and the built environment - to meet human material needs efficiently. Improved circularity metrics, encompassing social and systemic dimensions, would be of critical importance to provide a more holistic picture of progress and guide smarter interventions.

Fiscal and policy reforms should ensure that environmental and social costs are reflected in material prices. Current systems reward extraction-based growth, undervalue labour, and assign no market value to nature, leading to its destruction. Such misaligned incentives perpetuate economic, social, and environmental imbalance. To achieve social and environmental sustainability, production, finance, and consumption signals must all be oriented toward circularity.

The private sector increasingly calls for stronger material flow governance. While energy systems are already well covered, metals and minerals are not. A coordinated framework, similar to what exists for energy, is needed to manage materials, monitor flows and impacts, and harmonise policies.Systemic transition requires not only a successful energy transformation, but also a transformation of the entire economic model, from a wasteful and unfair one to one that meets our needs in the most resource and energy effective way. A true circular economy.

Already in 2014, the Commission recognised the need for lower resource costs, predictable supplies, and stronger competitiveness for re-industrialisation. It cautioned that Member States without national targets would struggle to develop balanced measures that address economic, social, and environmental impacts. Therefore, it proposed resource productivity targets, arguing that a realistic EU-wide target could drive policy coherence, competitiveness, and sustainable growth.5

An EU-level, non-binding target was proposed as a way to focus political attention, improve policy coherence, and unlock the circular economy's potential for sustainable growth and jobs. The Communication projected that with smart circular policies, resource productivity could increase by around 30% by 2030—double the business-as-usual forecast of 15%.

When the Juncker Commission abandoned material targets, resource productivity growth slowed to just 1.2% per year. Only with the first von der Leyen Commission and the launch of the European Green Deal did momentum return, lifting annual growth to 2.5% and putting the EU back on track to achieve the doubling of resource productivity by 2030.6

The current geopolitical and economic situations however require more than this. The business and investment community now sees the circular economy as inevitable and a source of competitive advantage. But to unlock the scale of investment required, policies must provide predictability, a level playing field, targeted financial support, faster decision-making, and simpler, more practical rules. Instead of deregulation, they need simplification, and for policymakers to not kill industry with kindness.

The need for binding targets and a consistent direction is clear. European competitiveness, security, and strategic autonomy all depend on sound material management. The Circular Economy Act represents a crucial opportunity to set a systemic course. Without decisive action, the EU risks seeing circularity rates rising by only a single percentage point by 2030 – a sign of stagnation, not success.

Janez Potočnik is a co-founder of the Systems Transformation Hub, Co‑Chair of the UNEP International Resource Panel and a partner at Systemiq.

The content presented in this opinion piece is solely those of the author in their personal capacity, and does not necessarily reflect the position of the Systems Transformation Hub or its members.